Infrastructure Architecture

JHub Apps, also known as JupyterHub (JHub) App Launcher, is an Externally-Managed JupyterHub service designed to enable users to launch various server types including API services, any generic Python command, standard JupyterLab instances, and dashboards such as Panel, Bokeh, and Streamlit.

High Level Overview

The system is built on FastAPI as detailed in the services.apps module. It initializes and runs through a Uvicorn server (a WSGI HTTP server), and is managed by the JupyterHub service manager upon startup.

This service operates on the Hub's host at port 10202 with a set number of workers as specified in the service_workers configuration parameter.

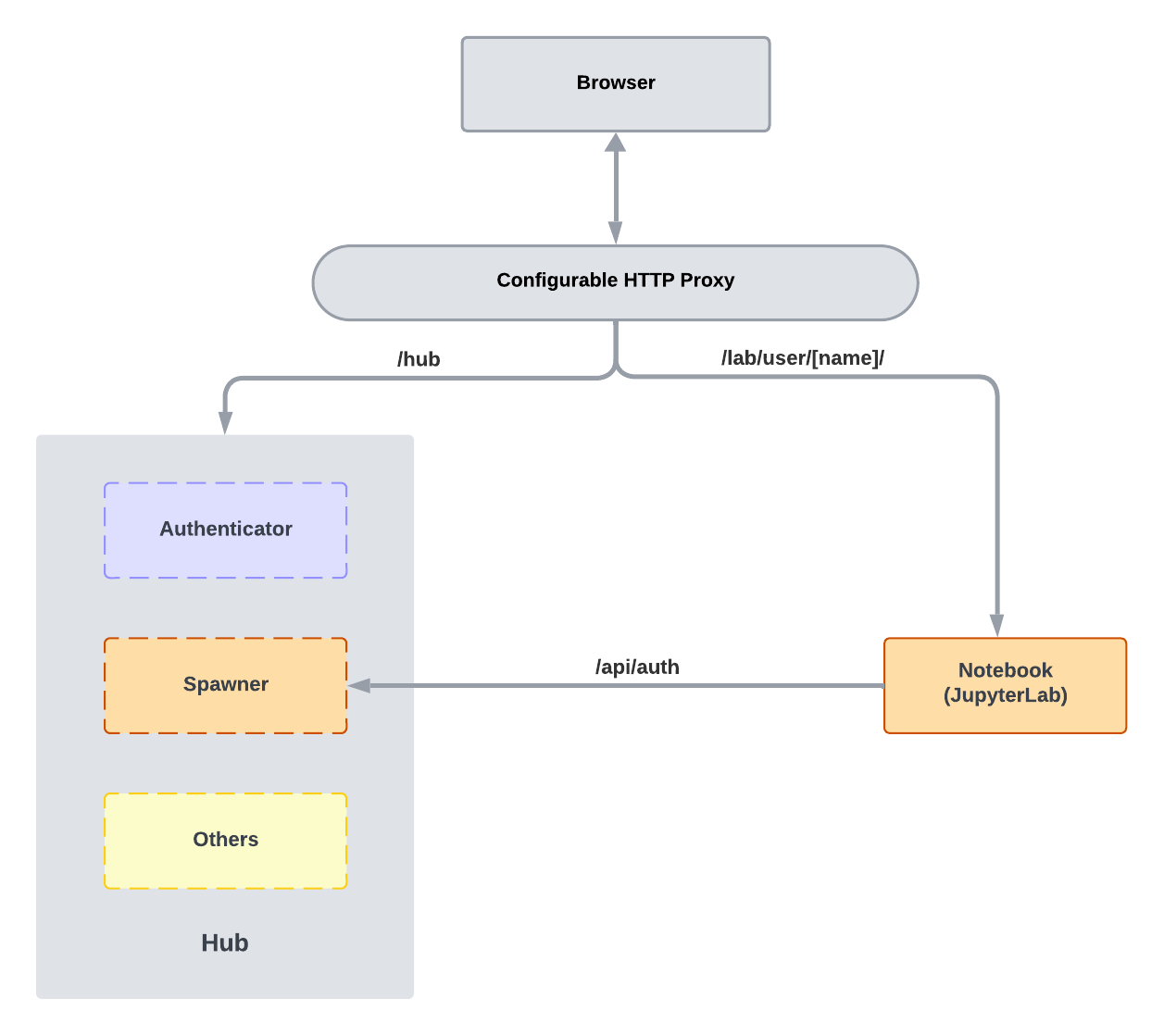

JupyterHub subsystems

Before we dive into the specifics of JHub Apps, it is essential to understand some basic concepts of JupyterHub's architecture. JupyterHub itself is comprised of four primary subsystems:

- Hub (tornado process) that serves as the core of JupyterHub

- Proxy configurable HTTP proxy that dynamically routes incoming browser requests

- single-user Jupyter notebook server (Python/IPython/tornado) managed by Spawners

- Authenticator an authentication module that governs user access

The most critical component of JupyterHub is the Hub, which manages the user's lifecycle, including authentication, spawning, and routing requests to the appropriate single-user server. The Hub also serves as the primary entry point for users, providing a web interface for logging in, selecting services, and launching single-user servers.

Then there is the configurable HTTP proxy, which acts as a gatekeeper, dynamically updating internal routing to direct traffic efficiently and securely to the appropriate server instance. This setup not only supports default proxies but also allows for custom proxy configurations to manage various external applications seamlessly.

Last but not least, the Spawners are abstract interfaces to processes that can start, monitor, and stop single-user servers. They are responsible for managing the lifecycle of the user's server, including spawning and stopping the server, as well as monitoring its status.

For more information on JupyterHub's architecture, please refer to the official JupyterHub Technical Overview documentation.

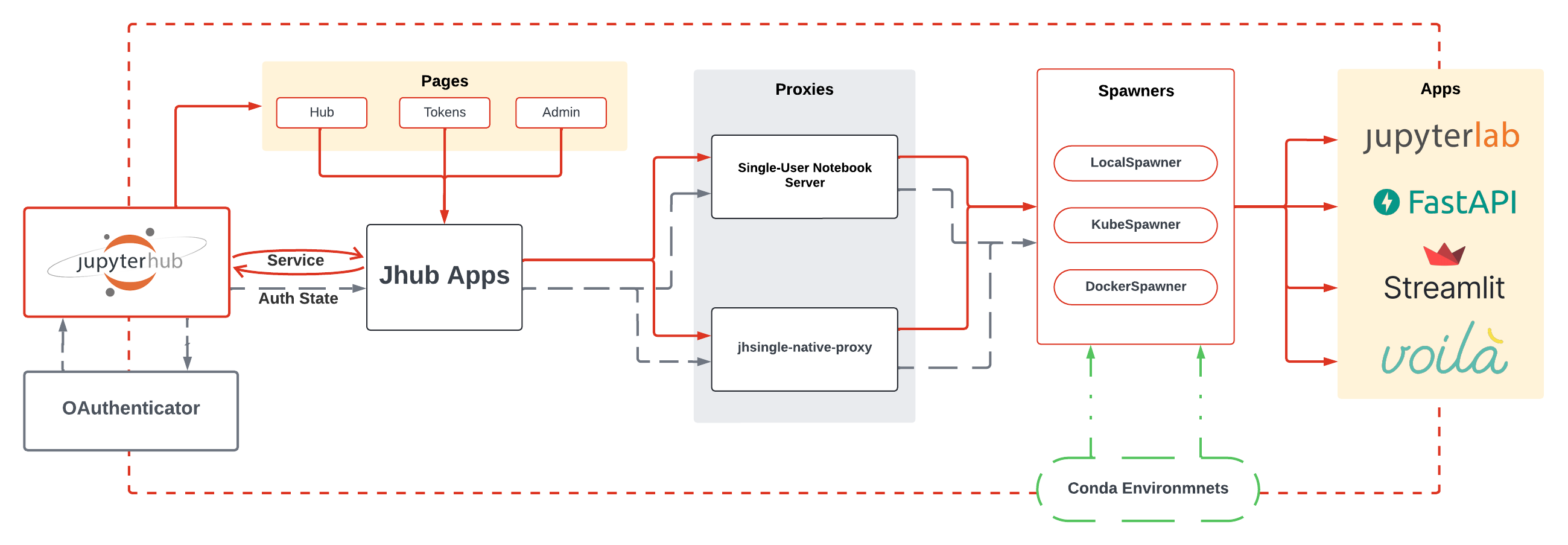

JHub Apps Integration

When JHub Apps is launched, it integrates into JupyterHub as a new service. This integration modifies the Hub's homepage to feature the service's URL, providing users with access to other services and control over deploying various apps beyond JupyterLab, such as Streamlit Bokeh, Panel and many others.

Throughout the following sections, these apps will be referred to as "frameworks," the main focus of the JHub Apps service. More information on supported frameworks and their configurations can be found under the create apps section.

The newly added JHub Apps service introduces intermediate steps to the JupyterHub subsystems lifecycle introduced above:

- The Hub initiates its own proxy server.

- JHub Apps is launched and registered within JupyterHub as an external service.

- The http-proxy initially routes all requests to the Hub, adhering to the extensions and modifications made by JHub Apps.

- JHub Apps modifies the Hub's homepage to include its URL (dynamically handled by the proxy), extending the service selection options for users to choose from various frameworks.

- The Hub continues to manage logins and server spawning.

- JHub Apps adjusts request handling to direct users to the appropriate single-user server environments based on their framework selections.

Technical Architecture Diagram

Below is a diagram illustrating the technical architecture of the JHub Apps service and its interaction with the JupyterHub system:

Starting from the left of the diagram:

- Users engage with the JupyterHub interface via their browsers, logging in through their preferred OAuth providers (e.g., GitHub, Google). Authenticated users are redirected to JHub's homepage, where they select and launch the desired service.

- As an external service managed by JupyterHub, JHub Apps service maintains full access to JupyterHub’s endpoint API's: authentication, authorization, and access controls. As a result, users still maintain the capability to visit Hub's built-in pages.

- On the homepage, users can choose the specific framework to deploy as a single-user server. JHub Apps then spawns the selected framework similarly to how JupyterLab is launched. The service redirects users to their individual server instances, where they can interact with their deployed application.

Looking Under the Hood

When a user selects a framework, JHub Apps balances the given requests into two possible proxies, each one corresponding to a different deployment type:

- For standard JupyterLab instances, the request is only managed by the default

jupyter-server-proxy, which

launches the JupyterLab instance, under your usual

/labURL. - For other frameworks, an additional proxy layer is launched within the web-service, the jhsingle-native-proxy, which works in a similar fashion as the above, but is designed to remove the dependency on the jupyter notebook and jupyterlab services, while also allowing for a direct connection to the selected framework (webs service) during its lifecycle.

Here’s a simplified explanation of the interaction between the two proxies:

- Public Proxy (configurable-http-proxy):

- Acts as a gatekeeper, for all receiving requests.

- This proxy decides where each request should go based on the user's information and routes it accordingly.

- Internal Proxies:

- jupyter-server-proxy:

- Jupyter Server Proxy lets you run arbitrary external processes (such as RStudio,

Shiny Server, Syncthing, PostgreSQL, Code Server, etc) alongside your notebook

server and provide authenticated web access to them using a path like /rstudio

next to others like

/lab.

- Jupyter Server Proxy lets you run arbitrary external processes (such as RStudio,

Shiny Server, Syncthing, PostgreSQL, Code Server, etc) alongside your notebook

server and provide authenticated web access to them using a path like /rstudio

next to others like

- jhub-single-native:

- Similar to the public proxy, it also dynamically updates the available route table, it is, allows a public facing endpoint to be created for the selected web-service (framework), though its main difference is that it is designed to be a lightweight proxy, removing the dependency on the jupyter notebook and jupyterlab services.

- jupyter-server-proxy:

How does all Work Together?

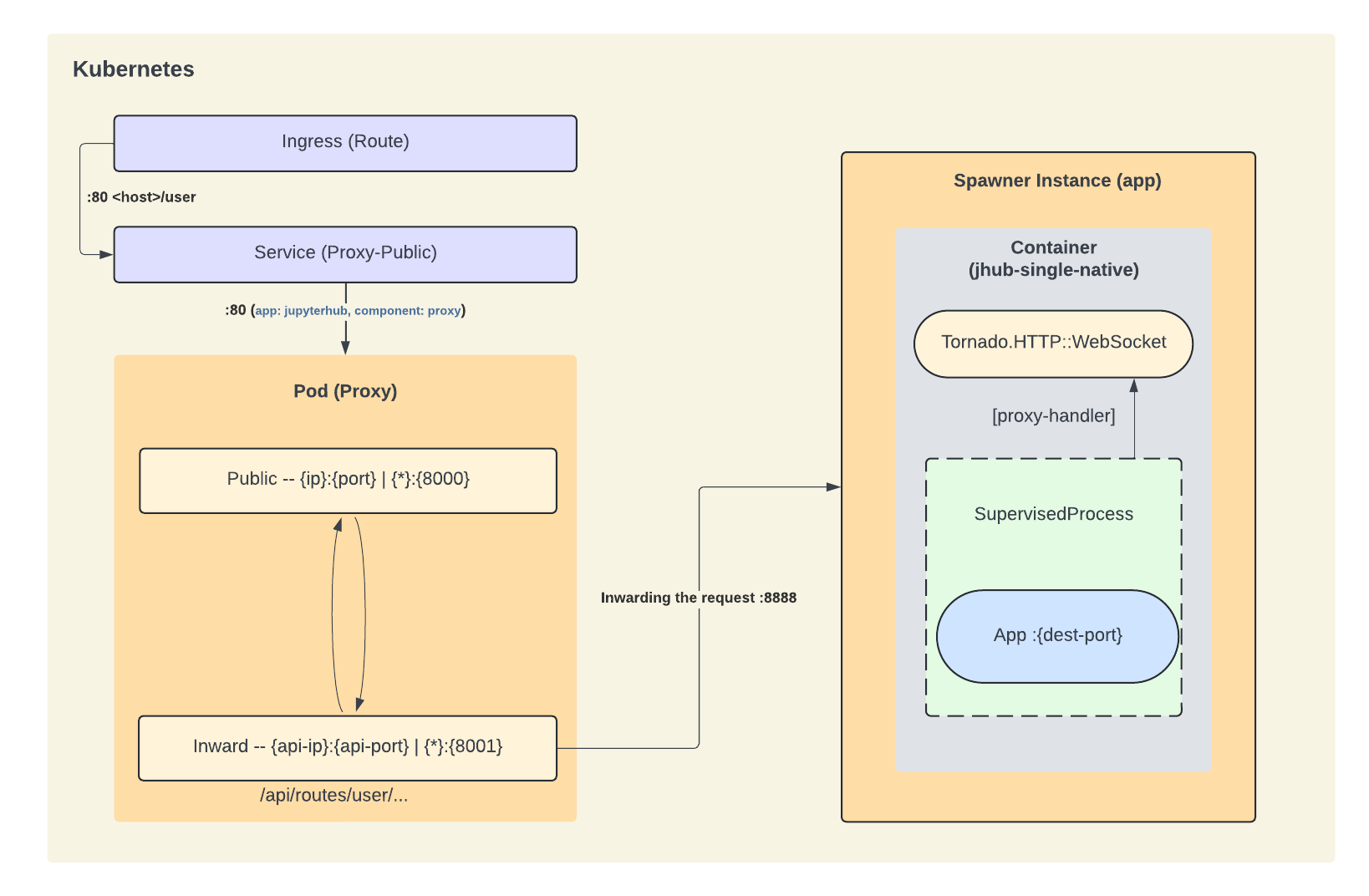

As an example, the diagram below illustrates the interaction between the two given proxies (http--jupyter-server-proxy or http--jhub-single-native), in a kubernetes environment.

To grasp the general concept of how the routing is handled, you can disregard the

specifics of the Kubernetes environment, such as the Ingress (Route), and Service (Proxy-public) in the diagram bellow:

- Request Handling:

- A user sends a request to access their selected framework through the JHub Apps home page.

- The public proxy receives the request and forwards it to the Jhub Apps service

internally, which then launches the selected web-service through the internal proxy

in a containerized environment.

- Based on the selected framework, we will end up spawning different proxies, as explained in the previous paragraph. Though, the overall routing logic is the same.

- The internal proxy then ensures that the user’s specific web application is available and properly set up, by wrapping its execution in a supervised process. While also handling a socket connection with jupyterhub's internal API for errors and to keep the heartbeat and the user's session running.

- The user interacts with their web application as if they were directly connected.